In Short:

On its surface, Revue Starlight is an anime about nine young women who attend an all girls music and stage production school. They learn to sing and dance and act and perform as you might expect. But, when they aren’t attending academic or artistic classes, these same girls are called to fantastical Revue auditions where they must literally fight each other, weapons in hand, in thrilling, character revealing, one-on-one musical stage battles for the right to be their class’ Top Star.

Revue Starlight, to its credit, is built around a detailed, veiled criticism of the Takarazuka Revue style of stage shows and music schools, but some viewers may be unfamiliar with these real world contexts, leaving them lost to the show’s finer points.

Suggested Minimum Watch: 1 episode. The first episode encapsulates both the mundane slice of life and fantastical Revue sides of the show well enough to let you know what you’re getting into.

Full Review:

It was the stage battles of Revue Starlight that first caught my eye. They looked like something out of a Magical Girl anime with flashy transformations and superhuman movements. That the show also seemed to focus somewhat on the behind the scenes aspects of a performing arts training school interested me, as well, since I tend to enjoy anime that really know their real world influences. In some ways, I got a bit more than I bargained for as you’ll see in the Dig Deeper segment at the end!

It was the stage battles of Revue Starlight that first caught my eye. They looked like something out of a Magical Girl anime with flashy transformations and superhuman movements. That the show also seemed to focus somewhat on the behind the scenes aspects of a performing arts training school interested me, as well, since I tend to enjoy anime that really know their real world influences. In some ways, I got a bit more than I bargained for as you’ll see in the Dig Deeper segment at the end!

In the first episode, we are introduced to eight girls who attend Seisho Music Academy. They do everything together from attending typical academic classes to participating in all the different dance, acting, and performing arts classes you might find at a music academy. For the most part, the cast is split into pairs early on. Our main character, the energetic yet lazy Karen Ajio gets paired up with the more reserved and responsible Mahiru Tsuyuzaki. The most accomplished dancer and actress in the class, Maya Tendo, often gets paired off with her competitive rival the French-Japanese Claudine Saijo. And so it goes. Each of these pairings end up carrying through the anime’s twelve episodes with transfer student Hikari Kagura throwing a wrench into the balanced mix by the end of the first episode.

In and out of class, the girls are relatively friendly, but there is an air of competition between some of them that complicates things. Others have different personal issues that need to be worked through. For instance, elegant hometown star Kaoruko Hanayagi’s over reliance on her long time friend Futaba Isurugi eventually becomes an issue. There’s also the soft spoken but intelligent and hard working Junna Hoshimi and the capable but surprisingly motherly Nana Daiba who form a strong bond later in the series after a shared revelation.

In and out of class, the girls are relatively friendly, but there is an air of competition between some of them that complicates things. Others have different personal issues that need to be worked through. For instance, elegant hometown star Kaoruko Hanayagi’s over reliance on her long time friend Futaba Isurugi eventually becomes an issue. There’s also the soft spoken but intelligent and hard working Junna Hoshimi and the capable but surprisingly motherly Nana Daiba who form a strong bond later in the series after a shared revelation.

If Revue Starlight were merely a slice of life show focused solely on these girls and their preparations for their upcoming stage show “Starlight” it would passable but a little dull. All the characters are generally likable, and there are minor conflicts, but there’s just no intense spark between any of them that makes you sit up and take notice. That’s because the show is saving its biggest emotions and character moments for the stage.

At the end of each day of classes, most of the girls receive a strange text message with the cute icon of a giraffe inviting them to special Starlight Revues. The girls enter a not normally there elevator within the school and are brought down deep underground to a giant circular stage surrounded by an even larger pool of water all beneath a bizarrely underground version of Tokyo Tower. Here, their singing, acting, and combat abilities(?!) are pitted against one another in one on one stage battles.

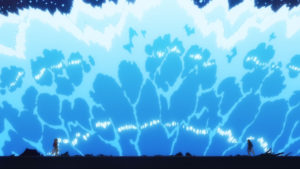

These Revues make up the core strength of the show. They are fantastical and highly reflective of each’s girl’s almost magical stage presence. The Stage of Fate they fight on often shifts and changes in response to the current combatants’ deepest thoughts and desires, and in response to who currently has the upper hand in the performance. Backgrounds, which can be anything from brightly painted cardboard flames to abstract city sets, often magically move in and out as if part of a stage play. The girls themselves transform as if they’re part of a Magical Girl anime. They fight in fancy military dress uniforms instead of the clothes they are wearing when they arrive at each Revue.

The girls clash their weapons and leap to impossible heights and dodge and tumble as part of these battles, but there is always a strong theatrical element involved. They move with a dancer’s grace and follow dramatic stage direction that sometimes even sees them coordinate their singing and dancing as if part of a stage musical. Despite the clang of weapons, there isn’t any actual violence in these Revues. I can’t remember even a single time that any of the girls actually get hurt in the several Revues they attend. Their goal isn’t to stab or maim their opponents. Instead, they try to cut the tie that holds their opponent’s cape-like overcoat on their shoulder so it falls to the ground.

The girls clash their weapons and leap to impossible heights and dodge and tumble as part of these battles, but there is always a strong theatrical element involved. They move with a dancer’s grace and follow dramatic stage direction that sometimes even sees them coordinate their singing and dancing as if part of a stage musical. Despite the clang of weapons, there isn’t any actual violence in these Revues. I can’t remember even a single time that any of the girls actually get hurt in the several Revues they attend. Their goal isn’t to stab or maim their opponents. Instead, they try to cut the tie that holds their opponent’s cape-like overcoat on their shoulder so it falls to the ground.

The Revues always feature two different girls paired off against each other, but the real thing keeping each Revue interesting is that they have a larger point than just seeing which girl is better with their chosen weapon. The Revues are not really about the physical combat at all. Instead, each Revue highlights the various girls’ interpersonal conflicts. One early Revue highlights how one of the girls came to see being on stage as a way to free herself from her childhood shyness and how her opponent’s newfound success threatens to take the shy girl’s stage, and confidence, away. Another Revue is squarely focused on demonstrating that one girl’s spirit and enthusiasm by themselves are not nearly enough to overcome another girl’s innate talent.

While these Starlight Revues are the heart of the show, Revue Starlight actually manages to tie its flashy combat back into its stage girls’ daily lives in interesting ways. The lessons about kindness, hard work, jealousy, and sacrifice the girls learn during their Revues often change them for the better off the stage. But, more than that, Revue Starlight tells a satisfyingly cohesive overall story with a couple of twists and turns along the way. I appreciate the way it broke up details about the Starlight Revues and about its characters’ motivations and backstories. You don’t learn everything all at once, but the pacing delivers new revelations almost on an episode by episode basis.

If I was to levy any criticism of the show’s plot, it’s that the school’s two top ranked stage girls, Maya and Claudine, don’t get the backstory episodes they deserve. Each has a big personality and have hints at compelling pasts, but we never dive in. And that’s a shame.

Oh, and I guess I should address the elephant in the room. Or, more specifically, the giraffe. These magical Revues are coordinated and overseen by a full-sized, deep-voiced, telepathic talking giraffe. It is the giraffe who introduces girls to the Revues and who sets the schedule for who battles who each day. Yes, his inclusion is strange, and while I don’t want to spoil everything about him, you should listen to what he says, as his plainly stated desires and love of the stage make up a small but important part of the show’s plot.

In terms of art and animation, Revue Starlight ranges from good to stunningly great. Once again, the Revues represent its heights. Most start with brilliant character introductions featuring larger than life statements of intent while a dazzling array of spotlights light up the screen in ways that left me breathless. The on-stage combat is also generally well done with nice use of sparks and some fun combat flourishes. Computer animation occasionally pops up, but generally only to animate the spotlights or provide a handful of really good sweeping camera moves that would be difficult to pull off with hand drawn animation alone.

In terms of art and animation, Revue Starlight ranges from good to stunningly great. Once again, the Revues represent its heights. Most start with brilliant character introductions featuring larger than life statements of intent while a dazzling array of spotlights light up the screen in ways that left me breathless. The on-stage combat is also generally well done with nice use of sparks and some fun combat flourishes. Computer animation occasionally pops up, but generally only to animate the spotlights or provide a handful of really good sweeping camera moves that would be difficult to pull off with hand drawn animation alone.

Outside of the Revues, character designs, and, oddly enough, some very tasty depictions of meals are Revue Starlight’s biggest strength. Each of the nine girls is unique and identifiable and some of the food that Nana “Banana” Daiba cooks for her friends just looks delicious.

The only real criticisms I have of Revue Starlight’s art is that the show is well known to have run out of time and budget by the end. It never gets bad, but if you pull yourself out of the moment and watch closely, it does become apparent that the breathtaking combat animations and scene changes of the show’s earlier Revues give way to slow pans across unanimated still shots by the final big battle. The show always reaches for greatness, and still delivers some excellent animation here and there even at its low point, it’s just unfortunate the creative team wasn’t given the budget or time necessary to fulfill the entirety of their vision.

Soundwise, Revue Starlight is uniformly excellent. I’d expect nothing less given that Yoshiaki Fujisawa is involved. His work on A Place Further Than The Universe and Land of the Lustrous was outstanding. The characters, here, have distinct voices and are well acted in both the Japanese and English language tracks. The songs the girls sing in the middle of their Revue battles are catchy and the lyrics they sing at each other are actually surprisingly important and impactful. “Star Divine”, the battle song for episode ten’s Revue, “The Star Knows” sung in the 2nd Revue, and “Re:Create” which plays a pivotal role in the 8th episode are all especially noteworthy. Be sure to turn on the song subtitles or you’ll really will miss out during the series. The song lyrics are very important since they are how each girl primarily expresses her mood and reason for becoming a stage girl.

Finally, I’d like to pay special note to Revue Starlight’s opening and its multiple closings. The opening starts with this nice look at the main characters set to a slow stage curtain opening before it transitions through fun slice of life moments and on to showing the type of combat featured in the Revues. The opening song Hoshi no Dialogue (Dialogue of the Stars) is great, too. The endings are neat in that most of the episodes have similar but distinct end credits sequences based on the primary character or characters who just took part in that episode’s Revue.

Finally, I’d like to pay special note to Revue Starlight’s opening and its multiple closings. The opening starts with this nice look at the main characters set to a slow stage curtain opening before it transitions through fun slice of life moments and on to showing the type of combat featured in the Revues. The opening song Hoshi no Dialogue (Dialogue of the Stars) is great, too. The endings are neat in that most of the episodes have similar but distinct end credits sequences based on the primary character or characters who just took part in that episode’s Revue.

All In All:

Revue Starlight is an interesting anime with a unique premise. The way which it uses its magical stage play Revues to resolve various emotional and status based conflicts between its cast members is like nothing I’ve ever seen before. I love that the songs being sung by the characters in the midst of combat often mattered as much or more than the action within their fantastical stage battles. If you love anime with music and theatrics, you should at least give this a one episode try.

Interestingly, Revue Starlight has yet another hidden side that really pulled me in. Almost everything in the show from the varied heights of its characters to the small pink lens flare glows that are present in almost every single background serve as a veiled criticism of the real world stage shows and music schools of Japan’s Takarazuka Revue. We’ll need to Dig Deeper and enter spoiler territory to really talk about this aspect of the show, but the basics are that Revue Starlight actually speaks out quite strongly against the 100+ year old practices of pitting actresses against each other in competitions where only a handful can reach the highly revered yet highly regulated position of a Top Star.

Interestingly, Revue Starlight has yet another hidden side that really pulled me in. Almost everything in the show from the varied heights of its characters to the small pink lens flare glows that are present in almost every single background serve as a veiled criticism of the real world stage shows and music schools of Japan’s Takarazuka Revue. We’ll need to Dig Deeper and enter spoiler territory to really talk about this aspect of the show, but the basics are that Revue Starlight actually speaks out quite strongly against the 100+ year old practices of pitting actresses against each other in competitions where only a handful can reach the highly revered yet highly regulated position of a Top Star.

Because of all this, I highly encourage you to watch Revue Starlight then come back here to learn more about the sharp criticisms it is voicing, or, if you aren’t afraid of spoilers, continue along with me and learn about the show’s hidden depths so that you can go in with a better understanding of everything you are about to see.

Revue Starlight is actually one of the more interesting shows with one of the most well organized subtexts I’ve ever seen. In addition to its already tightly woven plot about the power of a long held promise, just about every aspect of the show also works to demonstrate the flaws of the real world Takarazuka Revue system. This is going to require a bit of a history lesson, so bear with me.

The Takarazuka Revue is a stage show company that was founded in 1913 by a Japanese railroad tycoon in the city of Takarazuka, Japan. The city had become a tourist city at the final stop of a rail line and in order to further boost the city’s tourist potential, this tycoon created an all girls theater that quickly grew in popularity and status. The theater eventually formed the Takarazuka Music School, an elite acting school similar to the one in the anime. This school only accepts a few of dozen young women each year. The real life school is very strict and the actresses compete against each other to become one of the handful of “Top Stars” maintained by the company at any given time.

There’s an extra wrinkle there, though. Even though the company puts on a wide variety of shows with male and female parts, think Romeo and Juliet or Phantom of the Opera, all the parts are played by female actresses. To accomplish this, the girls joining the school are split up at the end of their first year into Otokoyaku (boy role) and Musumeyaku (girl role) groups. Sadly, only Otokoyaku are eligible to become Top Stars, and typically they are paired with a single Musumeyaku whose job it is to support their performance and popularity until they retire. Tragically, retirement usually happens just a few short years after an actress obtains one of the Top Star positions since it takes so long to reach that level and since once there, the actress is at the top. There’s nowhere left to go.

In the Takarazuka system, young women compete fiercely with each other while, right off the bat, half of them have no hope of earning the most money and fame because only the ones sorted as Otokoyaku even have the potential to become a Top Star. Those are just the rules. That sorting is almost entirely based on physical attributes such as height, vocal tone, and looks. Things like acting ability and singing ability are secondary. To be a Top Star, you have to fit a certain predefined mold and everyone else is treated as significantly lesser than the Top Stars.

Just as there is only a singe Otokoyaku in each troupe, there is also only a single Musumeyaku, as well. You’d think that would make them equal, but it doesn’t. In reality, there is enormous pressure put on the Musumeyaku to support their Otokoyaku. If there’s a mistake the Otokoyaku makes, the Musumeyaku takes the responsibility. If there’s an opportunity to boost the Otokoyaku’s popularity, the Musumeyaku is obligated to pursue it. It’s the Musumeyaku’s job to enhance the desirability and fame of their Otokoyaku, but the reverse is never true.

The Top Star is the only one who truly matters in this system, but there is a ton of pressure and isolation demanded of the Otokoyaku, as well. In the past, there were strict rules like no romantic relationships for anyone at the school, especially either the Otokoyaku or Musumeyaku pairs since they have to remain potentially available to all their fans. Girls at the school or in one of the troupes, especially the Otokoyaku or their Musumeyaku, were also forbidden from receiving or responding to fan mail as well. These kinds of rules and restrictions, combined with the fierce competition to become a Top Star, led to a lot of burnouts, bullying, lawsuits, and even suicides over the years. The Takarazuka Revue has cleaned up its image a good bit in the modern age, and it has cut back on some of its rules, but all these problems still linger over it to some extent.

We can see so many aspects of the Takarazuka Revue system within Revue Starlight. For instance:

Why are Maya Tendo and Claudine Saijo generally seen as the school’s two top students? Why does the always cheerful and motherly Nana “Banana” Diaba have the ability to surpass the both of them as seen later in the series? The answer is that Maya and Banana have all the physical attributes like height and stature they need to become Otokoyaku in the Takarazuka Revue system. Claudine comes close, but ultimately she is too girly and in the real world she would have been seen as a top performing Musumeyaku. And that’s exactly where she ends up! The way Claudine breaks down in episode ten and takes responsibility for Maya’s loss are classic Musumeyaku tendencies drilled into those counterpart women who are forbidden from reaching Top Star status. Sadly, someone as hard working and skilled as Futaba Isurugi would never be considered an Otokoyaku. I believe we see her lose out to Maya, Claudine, and even her friend Kaoruko over the course of the series for largely for these reasons. (Though her loss to Kaoruko is actually its own interesting character study… Their relationship was always based on Futaba supporting and following Kaoruko. If Futaba had won, it would have driven them completely apart which neither actually wanted.)

Similarly, look at the way the Revues are set up. The girls are all battling to become the Top Star, but we later learn that the Top Star usually robs their rivals of their Shine. This is one of the real world criticisms leveled at the Takarazuka Revue system. A small handful of women, one from each acting troupe, achieve Top Star status. These women are the ones to get the fame and press and money while all the other candidates are treated as mere actors. This can be devastating to those who fail to reach the exclusive Top Star position. Revue Starlight takes this even further as we see Hikari Kagura and later Karen Ajio straight up lose the will to continue their careers after losing out to their class’ Top Star. That Karen’s ultimate loss was to her best friend just made things all the more tragic!

With all this in mind, take note of just how often our main character Karen Ajio goes against the Takarazuka Revue system. Her promise to Hikari is for them to share the spotlight… in direct contrast to the Top Star system that recognizes one actress above all others. Her declaration at the end of her transformation sequence, “We will all do Starlight!”, sets it up for all her classmates to join her as equals on the stage which, again, is the opposite of the normal Top Star system.

In contrast, look at Maya and Claudine. Both of them never really had any competition until they met each other. And how do they eventually end up? As an Otokoyaku and Musumeyaku pair determined to claim their first and second place roles from within the Takarazuka Revue system! It’s not an accident that these two represent one of the final obstacle our main characters have to overcome.

It’s all this history and deliberate veiled criticism that I think propels Revue Starlight past its merely average presentation to become one of the more interesting anime I’ve had the pleasure to dig deeper into. But that’s not all there is to say. I didn’t know any of this when I started Revue Starlight, and I almost abandoned it because of that. But then, I caught a series of videos and articles that go into even more detail and saved the show for me:

- Under The Scope’s Building A Stage Girl: Behind The Scenes with Revue Starlight Staff and Staging The Story: The Visual Theater of Revue Starlight

- Emily Rand’s Atelier Emily blog has multiple articles discussing the symbolism of Revue Starlight.

- Andrea Ritsu’s Between The Revues series focusing on the origins and problems with Takarazuka Revue